stop making me defend Taylor Swift

On showgirl-shaming, 5,000-word essays hoping to out artists, mythologizing pop stars, and still pondering the true meaning of LCD Soundsystem's "Someone Great."

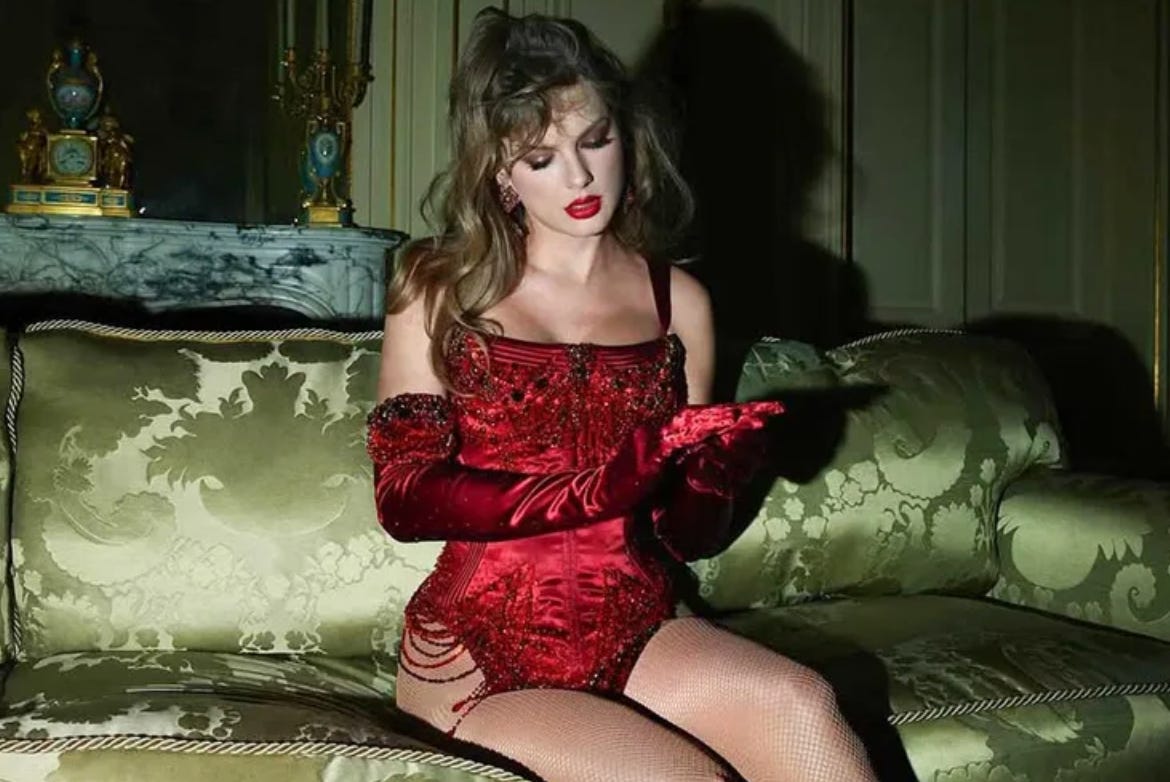

Yesterday, The New York Times published the op-ed, “Taylor Swift Is No Showgirl.” The author, Lissa Townsend Rodgers, who has thought and written a lot about showgirls, takes Swift’s new album title, The Life of a Showgirl, literally in order to make a reported essay on showgirls work. This makes the argument of the piece pretty flimsy. Were we to take every single title of Swift’s discography and make it a think piece, then other titles might read, “Taylor Swift isn’t fearless,” or “Taylor Swift doesn’t belong to the tortured poet’s department,” or “There’s no folklore in Taylor Swift’s Folklore.” We could go on and on.

“Ms. Swift has talked about the exhilaration and exhaustion of the Eras tour, changing costumes and dodging set pieces from Glendale to Gelsenkirchen, hustling through her paces alongside a coterie of dancers, a band, and a slew of techs and grips,” Rodgers writes. Though Swift may be a billionaire, she also wants people to know she works hard. But that fact alone is a departure from the showgirl archetype. “Showgirls may have a solo spotlight moment, but they don’t run the show. Onstage, it’s glitter, precision, and multiplicity. Backstage, rows of adjacent identical dressing room mirrors reflect rivalries and confidences, and there are no handlers or personal assistants, just co-workers fastening the back of a neckpiece or lending an extra pair of tights.”

To Rodgers, Swift is not a showgirl; she’s a star. It’s unclear if Swift’s use of showgirl costumes and album title is meant to literally convey that she’s just like any ol’ chorus girl hitting her marks three hours a night, sometimes twice a day, exhaustedly falling asleep hours later, then waking up and doing it all again. But from Rodger’s purview, she simply doesn’t earn this title.

I’ve previously written about Swift being named ‘Person of the Year’ by TIME. That she is forever ascending in her career and has been awarded and received critical acclaim for her accomplishments was my way of saying, Why give her this title again? Sure, she’s resilient, but she has long had resources most people do not have, and with each return from yet another pop star obstacle, she usually sees the efforts of her hard work and hardship pay off. That too isn’t entirely realistic. But we celebrate her anyway because she’s generally a good example to young people and appears to be generous and kind. But for grumpy babies who are her age (me), I would be remiss not to bring attention to the fact that other people do exist, each one doing extraordinary things and worthy of equal attention and praise.

I never said Swift was wrongly painted as a defiant woman. She is. That her audience assumes she’s just like them is kind of insane, because she isn’t. We mythologize her. Yes, we take cues from her. But then we take what she says and does, and we make it holy.

We need stars who shine brightly and appear to be something we can aspire to, transcending all the negativity and darkness in the world. But it’s one thing to place her in the context of reality in order to emphasize the accomplishments of others, and another to needlessly ridicule her based on something as silly as her album title.

While still at its peak in 2010/2011, I worked at the Downtown Brooklyn American Apparel store, where we could be found on any afternoon bopping our heads in our chiffon blouses tucked into shiny nylon pants while finger spacing clothes hangers to synth-y songs like “Someone Great” by LCD Soundsystem. Until someone told me the song was actually sad and about getting an abortion, or was it a miscarriage? Wait, wasn’t that Ben Folds Five? Actually, it’s about depression. No, it’s clearly about death. The truth didn’t seem to matter. That we were engaging with the song and creating a story that fit our worldview based on our experiences mattered.

Experiencing art, if believed to be a subjective process, doesn’t give us meaning. We give it meaning.

In January 2024, Anna Marks wrote The New York Times op-ed “Look What We Made Taylor Swift Do,” which I thought should be titled “Look What Taylor Swift Made Me Do.” In a 5,000-word essay, Marks, who is an Opinion editor for The New York Times, enumerates the many ways in which Swift has not only made queer art but has possibly outed herself numerous times without ever having officially come out.

There is a wealth of evidence. Marks cites songs by Swift whose muse “seems to fit only a woman” and evading end-rhyme in lyrics like “didn’t read the note on the Polaroid picture / they don’t know how much I miss you” from the song “The Very First Night” with Marks noting “her” not “you” would rhyme. In her music video for “You Need to Calm Down,” Swift incorporates colors from the Bisexual flag —pastel pink, purple, and blue—and, again, uses the same colors in a beaded friendship bracelet with the words “PROUD” in a picture posted to Instagram.

On stage, Swift has depicted herself as trapped in closets. In one particular scene from her show, a ladder appears, evoking a similar cover of The Ladder, an early lesbian publication from the mid-20th century. It’s easy to believe it could all be deliberate—these “dropped hairpins,” as Marks calls them, which are subtle clues one uses to convey their sexual preference to others.

Years ago, I wanted to believe, too. Despite identifying as straight, I understood and continue to understand the appeal of a pop star discreetly communicating her true identity through lyrical subtext and imagery. The release of Lover made it almost impossible not to believe that the release of the album’s first single during Pride month and its inclusion of notable figures in the LGBTQ community wasn’t signaling something bigger. I learned about the undertow of online “Gaylor” lore and a detailed PowerPoint presentation initially posted on Tumblr titled “Reputation is about Karlie Kloss.” A comprehensive guide to the gayest album.” And this was before the release of Lover, the album most referenced in Marks’s op-ed. I want this to be true, and maybe it is. But outside the subjective experience of interpreting song lyrics like “Someone Great,” there is objective truth. Doesn’t that matter?

Marks acknowledges that in a 2019 Vogue interview, Swift states that she is not a part of the LGBTQ community. “Rights are being stripped away from basically everyone who isn’t a straight, white, cisgender male.” She quotes Swift as saying, “I didn’t realize until recently that I could advocate for a community that I’m not part of.” But this statement of truth doesn’t dissuade Marks’s timeline of Swift’s increasingly overt flirtation with her alleged queer identity. Instead, she writes that Swift’s statements aren’t an outright denial. Somehow, it’s unclear if Swift is saying this because she’s straight and cisgender or “because she was stuck in the shadowy, solitary recesses of the closet.”

I appreciate the academic rigor with which Marks has artfully disentangled queer themes and theories from Swift’s work. But this is nothing more than an interpretation of Swift’s art, not necessarily Swift herself. Swift’s never confirmed she is queer. She has denied it. That her art speaks to a collective overlooked and underrepresented is real and meaningful. All of her fans can and should view her work through whatever lens they choose, but haven’t we learned that speculating on sexuality, whether it’s to hurt or confirm our own suspicions and bias, to feel part of a larger whole, is dangerous?

Marks writes that Swift has created a “dollhouse” for her fans, with her art languishing in “a place of presumed statis.” She questions what the cultural response might be if we “made space” for Swift to burn that dollhouse, as if there will be a time for Swift to interject her queer identity fully. For Marks, undeniable queer visibility is a “radical act of resistance” which, in turn, helps make space for those without power. Swift is being called upon to emerge as a hero that she might not be.

As much as I don’t want to defend Taylor Swift, I feel that I need to. She can’t win. She is either criticized for laying claim to something she isn’t or criticized for not owning an identity someone assumes is hers. Look, we need bright spots where we can find them. But do we need our bright spots—even our pop stars—to be everything we want them to be?